Table manners: Unexpected grace at communion

Communion is a vital part of my week. My tradition, the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), has staked its identity on the weekly celebration of the Lord's Supper. Each week we celebrate an open table: anyone who wishes to follow Christ is invited to receive the bread and the cup.

This is not the practice, of course, in the Catholic mass. There, only Catholics are welcome. And while I disagree with these rules, I respect them—so I abstain.

But I don't sit passively alone during communion at a mass. In the face of the Catholic Church's theological claim, I like to make a counterclaim of my own. I go forward, and when I reach the priest I cross my arms over my chest. This is the official signal that I am either a Catholic in need of confession or not Catholic. Instead of the body and blood of Christ, I get the door prize: a sign of the cross and a blessing.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

My gesture usually catches the priest off guard. It makes me uncomfortable, too. Typically our eyes meet, a moment of indecision passes, confusion results, and I stutter-step my way down the line sans bread and wine. For me it's a little Protestant protest, a small interruption in the normal flow of "the body of Christ, the blood of Christ." In that moment, the priest and I are both confronted with my exclusion, with the fact that in this church, I am a second-class Christian.

Last summer, however, I toned down my quietly radical ways. I spent the summer in Bosnia, studying religion and reconciliation in the Balkans as part of my divinity school education. I went to the region to make observations, not waves. When I found myself in a Catholic church on Sunday morning, I was content to restrict my eucharistic protest to silent prayer.

My studies took me to the broad Austro-Hungarian boulevards of Belgrade. I was invited by a Sarajevo-based interfaith choir—made up of Catholic, Orthodox, Muslim and atheist singers— named Pontanima to travel to the Serbian capital to witness the reconciling potential of religious music. One stop on the itinerary was to lead worship at St. Anthony of Padua Catholic Church.

As the mass crescendoed toward its eucharistic climax, the choir filled the sanctuary with a wide array of dynamic Orthodox chants and sublime Catholic hymns.

But as beautiful as this harmonic symbol of unity was, it proved to be fleeting. Once the conductor's baton brought the music to a halt, we were back to business as usual.

The priest consecrated the host, and some folks rose to receive the bread and the cup. Those of us who weren't invited remained in our pews. Catholic was divided from non-Catholic, insider from outsider. Religion's power to harmonize and unite lasted as long as Pontanima could hold the low drones of Rachmaninoff's bass line; its capacity to divide and exclude was never far away.

Disappointed by this reminder of religion's ambiguity, I watched the line form in the center of the sanctuary. I pressed my knees to the side to let my Catholic neighbors pass by me, and I lowered my head to pray my little prayer of Protestant protest.

When I lifted my eyes, I saw a portly man in a white robe scurrying down the side aisle. His eyes sought me out with an innocent and quizzical look, like a little boy searching for his parents in a crowd. His glasses bobbled down his short, round nose as he raced down the aisle—too quickly for a priest, too quickly for a 60-year-old man.

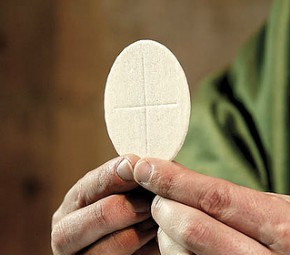

The whole scene was awkward. With 20 or so people still in line to receive the Eucharist, this Bosnian Franciscan took a handful of the host and sought me out of the crowd. Nearly out of breath, he lifted the small plate toward me. I stood up from my pew.

"Will you have communion?" My heart beat faster, the way it does if you get asked to speak when you're not expecting it, or when you're breaking a rule and know you may get caught.

I muttered, "Yes, I will."

"Christ's body, broken for you." He placed the host in my hand. I raised it to my lips and carefully set it down on my tongue. It stuck to the roof of my mouth and began to dissolve, flesh to flesh. As the priest returned to the rest of his flock, I felt the emotion welling up from my gut into my throat and reaching up toward my eyes. My head fell again in prayer—not of protest this time, but of gratitude.

I imagine this is what the prodigal son felt when he watched his aged father risk looking like a fool as he sprinted out to meet his son. Priests don't run during the mass; they certainly don't leave the 99 sheep behind to seek out the one who's lost, the one who needs to feel the warm embrace of full inclusion in a Christian community.

Phrases like "radical welcome" and "Christian hospitality" are popular these days; back home in Chicago it seems that I hear them in church almost weekly. They can become routine, milquetoast clichés that don't mean much. But in a world marked by violent ethnic strife, cantankerous political divisions and toxic racial segregation, the Lord's Supper has the potential to be a powerful and hopeful alternative.

My "first communion" reminded me that the God who shows up at communion is a God who brazenly—even foolishly—seeks us out of the crowd. A God who awkwardly crosses divisions and differences to invite each of us to full participation in life with God.