The biggest fish story

I am not an experienced fisherman, but some years ago I went with a friend on his annual trip to a remote lake in Canada. We spent most of a week at the family fishing cabin on an island surrounded by a vast expanse of water. The boat trip to the island took more than an hour. We fished from morning to evening. In the evening we prepared, cooked and ate the day's catch. In the cabin hung a homemade plaque that read: "Walleye—Tastes Like Cake." It was true.

After dinner, in the dark and around a fire, we told fish stories from the day. My stories were mainly about my ineptitude as a fisherman—how I almost steered the boat onto rocks, how I climbed a cliff with fishing lures stuck in my pocket and suffered the predictable prickly consequences.

Read our latest issue or browse back issues.

As I say, I am not a real fisherman. But it was easy to enjoy myself that idyllic week. Our boat rocked on the surface of crystalline blue water. The sky was wide and open and empty even of jet contrails. Our hours on the water were punctuated by sightings of bald eagles and sonically backgrounded by the calls of loons. I even caught a few fish.

And who can help being fascinated by fish? They are strange, blank-eyed, implacably silent, enigmatic and slippery creatures from another world—hard to grasp both literally and figuratively. Theirs is a submarine world, a world hidden and dark and deep, so different from our dwelling in the transparent medium of air. Fish, in all their sizes and shapes, come to us as emissaries from beyond, ambassadors of another existence.

Around that Canadian campfire and elsewhere, I have heard some fish stories in my day. And I had some awareness that the Bible mentions fish frequently. But I had not realized until this past Easter how deeply the symbol of the fish penetrates the Christian story and in fact goes all the way back to its beginning. During the Great Vigil of Easter, we Episcopalians read a lot of the Bible. It was during our last vigil, and readings from the story of Noah and the flood, that I noticed for the first time something unique about fish.

In Genesis 7:14, Noah invites onto the ark "every wild animal of every kind, and all domestic animals of every kind, and every creeping thing that creeps on the earth, and every bird of every kind—every bird, every winged creature." And in Genesis 8:17, after the flood has ceased, Noah and his family emerge from the ark with "birds and animals and every creeping thing that creeps on the earth."

These passages and their wording, of course, mimic Genesis 1 and the creation of the world and all its creatures. That is, they mimic Genesis 1 with a single exception. Genesis 1:20–23 notes the creation of birds and also of "the great sea monsters and every living creature that moves, of every kind, with which the waters swarm."

But on Noah's ark there is no aquarium. Alone among "all flesh," the fish are left to fend for themselves. While fish are not always spared the effects of God's judgment in the Bible, they are uniquely equipped to survive the judgment of the flood. Under this judgment they not only survive but thrive.

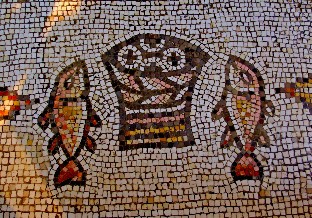

So it is that in the earliest chapters of the Bible fish become a sign of salvation, able to pass through judgment unscathed. Later, in the tale of Jonah, a fish scoops up the debarked prophet and carries him to safety. Once again a fish survives judgment, and this time bears another along to his salvation.

In the Gospels, Jesus echoes the story of the dunked prophet and declares himself a bearer of the sign of Jonah. He multiplies the loaves and fishes to feed multitudes. He calls as his followers no fewer than seven fishermen. He declares himself and his followers to be fishers of people.

So the fishy resonances—upon which I barely touch here—resound throughout scripture. Then they splash well beyond the pages of scripture. The early church made the fish a symbol of baptism, implicitly recognizing how fish survive the waters of judgment. Soon enough, it noticed in the Greek word for fish an acronym—ICHTHUS—for "Jesus Christ, God's Son, Savior," which made Jesus himself a fish, the ultimate emissary from another world, the Jonah-fish bearing all to ultimate salvation. So it is that he whose body we eat at the Eucharist himself swallows us up, incorporating us into his body and carrying us through chaotic seas to a distant shore we cannot attain on our own.

This is the biggest and best fish story of them all. It makes all the difference in the world that it is true.