Century Marks

Presidential prognostication: In a 1958 essay published in Esquire magazine, Jacob K. Javits, a liberal Republican senator from New York, predicted that the U.S. would elect its first black president in 2000. This president, he imagined, “will be well-educated. He will be well-traveled and have a keen grasp of his country’s role in the world and its relationships. He will be a dedicated internationalist with working comprehension of the intricacies of foreign aid, technical assistance and reciprocal trade.” Javits also predicted that “despite his other characteristics, he will have developed the fortitude to withstand the vicious smear attacks that came his way as he fought to the top of government and politics” (Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s introduction to Barack Obama: A Pocket Biography of our 44th President, by Steven J. Niven, Oxford University Press).

Teachable moment: The unraveling of the Ponzi investment scheme run by Bernard L. Madoff has caused turmoil at Jewish institutions and prompted a renewed discussion of ethics at Yeshiva University. Madoff was a board member of and a generous contributor to the Orthodox Jewish university, and Yeshiva lost about $110 million which it had invested through Madoff’s firm. In the wake of the scandal, some students have talked of feeling the pressure of competing values: on the one hand they are encouraged to live moral and religious lives, but on the other hand they feel pressed to succeed financially—so much so that they are driven away from public-service professions into high-paying careers. “In elevating to a level of demiworship people with big bucks, we have been destroying the values of our future generation,” says Rabbi Benjamin Blech, who teaches philosophy of law at Yeshiva. “We need a total rethinking of who the heroes are” (New York Times, December 23).

Learning curve: Greg Mortenson, author of the best-selling book Three Cups of Tea, has a new job: advising the U.S. military on how to fight Islamic extremism. In his book, Mortenson, whose Central Asia Institute has built 78 schools in remote regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan, criticizes the military’s efforts in Afghanistan, saying that the cost of a Tomahawk cruise missile ($840,000) would be better spent building dozens of schools instead. After General David Petraeus read Three Cups of Tea, Mortenson’s advice has been sought by the military on how to work with village elders and leaders. “There is a positive learning curve in the military,” says Mortenson. He refuses to accept military funding for his institute (Wall Street Journal, December 26).

Older and wiser: Henry Alford, 46, has written a book about old age based on conversations with more than 100 people over 70 (How to Live). Harold Bloom, the acerbic literary critic, told Alford that what he has gained with age is “a healthier respect and affection for my wife than I used to have.” Althea Washington, a retired school teacher, lost her husband and house in Hurricane Katrina and now lives in a small apartment close to train tracks. When asked how she’s coping, she responded: “Can you hear that train? As long as it stays on its tracks, I’ll stay on mine” (USA Today, December 30).

Take the pledge? A study conducted at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health concludes that teens who take a chastity oath are just as likely to have sex as those who don’t—and they’re less likely to use protection. In fact, those who took the pledge were 10 percentage points less likely to use condoms than nonpledgers. Pledgers don’t differ from nonpledgers in the age at which they become sexually active. According to researcher Janet Rosenbaum, “Abstinence education comes from this idea that if you teach birth control, that’s going to cause kids to have sex.” But dozens of tests show that this notion doesn’t have “any basis in reality.” She says parents talking repeatedly with their children about sex—including about contraception—is the most effective means of delaying sexual activity (Time, December 30).

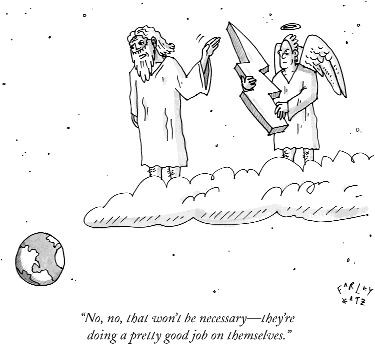

Creation care: Sir John Houghton may be the most important scientist you’ve never heard of. Until his semi-retirement in 2002, he was one of the leaders of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, an environmental study group created by the United Nations. Houghton, who believes we only have seven years to avoid global calamity, began investigating global warming over 40 years ago. A devout Christian, Houghton thinks global warming is as much a spiritual and moral problem as a scientific one. “If the Old Testament prophets were here, they’d be tearing their hair out, cursing us, telling us we’re absolutely greedy, and they’d be right,” Houghton says. He remains optimistic because he thinks the technology and funding exist to solve the problem and that scientists are committed to working on it. And he is sustained by the belief that God cares for creation (OnEarth, winter).

Bankrupt churches: Churches are increasingly finding themselves in the same financial bind as home owners—unable to pay off large mortgages and facing bank foreclosures. According to one study of 115 counties in the U.S., 0.31 percent of churches have received foreclosure notices, but the percentage is much higher when churches without mortgages are excluded from the data. In many of these cases the lenders were betting on the assumption that the congregations would grow in size and so have larger budgets to draw on for paying off mortgages. The lenders also assumed that churches would feel a moral obligation to pay off their creditors. While some say church attendance tends to increase during hard times, newer congregants don’t give as much money as longer-standing ones. One bit of good news for churches that lose their buildings: they usually are able to find facilities to rent (New York Times, December 27).

Behind the surge: The decrease in the monthly death rate of Iraqi citizens is credited by some to the military surge. But Juan Cole, an analyst on Iraq, says that the death toll decreased in large measure because the Shi‘a Muslims forced hundreds of thousands of Sunnis out of Baghdad. When the war began, Baghdad was split about 50-50 between Sunnis and Shi‘as; now it has a Shi‘a majority of 75 to 80 percent. “A Shi‘a militiaman in Baghdad would have to drive for a while to find a Sunni Arab to kill,” says Cole (on Cole’s blog, Informed Comment, December 26).