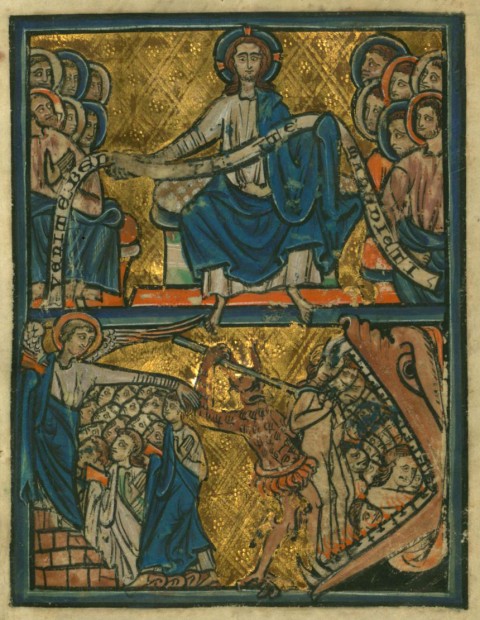

Reign of Christ Sunday (Ezekiel 34:11-16, 20-24; Psalm 95:1-7a; Matthew 25:31-46)

Does our discomfort over God’s judgment come from the fear of taking sides? Or the fear of being found on the wrong one?

As we approach the season of Advent, we find Ezekiel being outrageous in true prophetic style. If we pride ourselves on being spiritual seekers, Ezekiel insists that it is God who seeks us out and not the other way around. Can’t we prize the maturity of knowing who we are and of finding communities where we feel at home? Ezekiel informs us that we are in fact so lost that God must take the trouble to find and rescue us. Some of that sounds good—the idea that God desires to feed us, wipe away our tears and bind up our wounds—but it also makes us uneasy. Are we really that needy and so unable to help ourselves?

As often happens when prophets speak, closely following on the heels of the good promises comes what we perceive as bad. This talk of judging, of sorting out the sheep, sounds negative and even dangerous. It’s not healthy to think in terms of “us” and “them,” of those who pass the test and those who don’t. Yet this touches on what makes Ezekiel a prophet to begin with; he forces us to question whether our discomfort over God’s judgment comes not so much from fear of taking sides, or of being found on the wrong side, but from feeling affronted. Isn’t it our prerogative to label and condemn? We certainly act as if this is the case. Even people who describe themselves as nonjudgmental are quick to adopt the easy polarizing that marks contemporary discourse in America. Before we agree to listen to someone, we want to know if he or she is liberal or conservative; Democrat or Republican; gay or straight; hot or, God-forbid, not.

Ezekiel calls us on our folly. Judgment belongs to God, and God’s concerns are not our own. When God begins the sorting of the flock, it is not to divide the good from the bad or administer litmus tests of faith or political conviction. God is seeing what we have refused to see, seeking out the weak who have been butted around on their way to the feed trough. God pities those whose have been wounded by the selfish actions of others. This is the good news that any prophet worth the title conveys to us. It demonstrates why we need prophets in the first place.

Psalm 95 provides another glimpse of a God who is not like us, a God who made the sea and formed the dry land. We kneel instinctively before the One whose power is greater than we can imagine, and whose tenderness toward us is beyond our comprehension. Imagine a God who rules the universe, yet cares for us as we are. It sounds too good to be true, and our suspicions rise when we look at the gospel, which returns us to the theme of judgment. This God who sees us more clearly than we see ourselves is the One we will meet at the end of days.

On to Matthew’s judgment—always fun to preach as malls gear up for the Christmas rush and cash registers ring with false cheer. This stark account of the second coming allows us to reflect on what truly matters in this season. It helps to see the gospel in the light of Ezekiel’s witness. Just as the prophet warns us against claiming for ourselves tasks that are reserved for God alone, Matthew tells us that we are to take on other tasks on God’s behalf, chores we may not want. If the judgment in Ezekiel has to do with what God does, the judgment here speaks to what we are to do in the present, if we truly believe that Christ is among us.

We are to act as if Christ is in other people, even the stranger whom we believe we have reason to fear, the prisoner whose acts we find reprehensible, the sick we’d rather condemn because we’re convinced that their lifestyle contributed to their illness, the hungry who should have been able to fend for themselves. If we cannot recognize Christ in these others, what we have, to paraphrase the prison guard in Cool Hand Luke, is a “failure to imaginate.” Having been unable to see what God has placed before us, we now cannot act on what we haven’t seen.

The exercise of our imaginations is vital if we are to find Christ in others. But it is also necessary that we utterly reject the temptation to sloth, that perversion of imagination which gives us, in the words of Fred Craddock, “the ability to look at a starving child . . . with a swollen stomach and say, ‘Well, it’s not my kid.’ To look at a recent widow . . . and say, ‘It’s not my mom.’ Or to see an old man sitting alone in the park and say, ‘Well . . . that’s not my dad.’ It is that capacity of the human spirit to look out upon the world and everything God made and say, I don’t care.”

Craddock invades our comfort zones, as a preacher (or a prophet) should. And we may respond defensively: “I’m a good person, and I do care.” But how does that hold up to Ezekiel’s warnings and the Son of Man who comes in glory? “When was it that we saw you, Lord?” we ask, dumbfounded. The beauty of the question is that it is asked by both the righteous, who are unaware of the good they have done, and by the accursed, who are unaware that they’ve done anything wrong. And this is the heart of the matter. The human imagination, battered and torn by our fears and limitations, comes from a God who asks us to see ourselves and our world in a new way. How we choose to return this remarkable gift to God is entirely up to us.